The First Sunday of Lent (Year A)

In his novel Brighton Rock, Graham Greene wrote, “You can’t conceive, my child, nor can I or anyone, the appalling strangeness of the mercy of God.” Lent is the time when the Church pauses to reflect on the reality of that mercy. And, when weighed against human standards, God’s mercy is appallingly strange because it costs us so little: God asks only that we surrender to his love and mercy.

But this is counterintuitive for us, because most of us expect consequences for actions, rather than forgiveness. This is often because we struggle to forgive ourselves or to forgive others when they have offended or hurt us. Why should God be any different? And yet God is different—and that is what can make this process of surrendering to God’s mercy so hard for us to trust and believe in. The idea that God’s love is freely offered—to the faithful and the unfaithful, to the strong and the weak—directly confronts our instincts about fairness and control.

For most of us, this process of “surrender” is one which unfolds gradually over the course of a life of prayer, service, struggle, and even setbacks. However, the temptation to choose our own way and will over God’s is never far away. And we can see the results—the consequences—of these selfish or self-centered choices all around us. This lesson is at the heart of this Sunday’s First Reading, as we hear the story of Adam and Eve and their fall from God’s grace in the Garden of Eden. It’s an important story for us to spend some time reflecting on because the fault—that original sin—wasn’t about eating the fruit of the tree. Their fault was their lack of trust and their desire to control, giving in to the lie that “You will be better off deciding for yourself.” It’s something we face today when we say, “I know what God asks, but I’ll decide what’s right for me—for now” or, even, “I deserve this!”

The call to surrender to God’s mercy is at the core of the Christian life. And yet, at the same time, there is a struggle that takes place in every human heart—a daily tension between trust and control, between surrender and self-sufficiency.

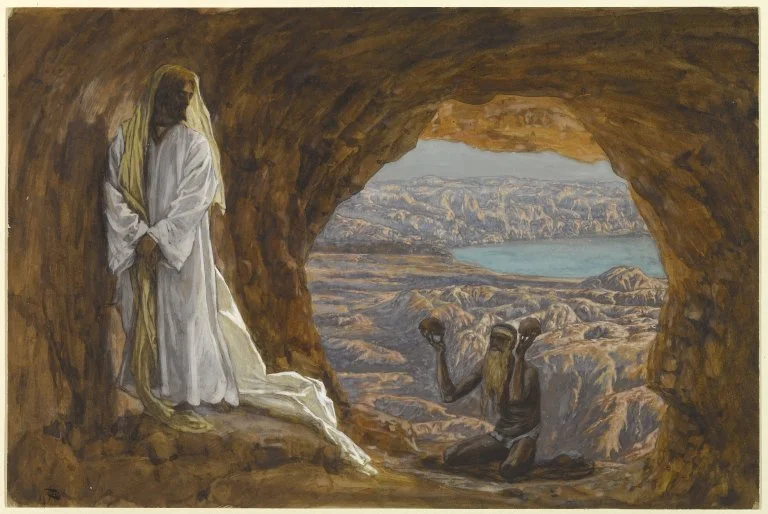

Saint Matthew’s account of the temptations of Jesus (which we hear in this Sunday’s Gospel) reminds us that the life of a disciple includes contending with the mysterious tug of evil, which is both repellent and attractive. Just like Jesus, we are tempted to temporarily shift our focus—perhaps, just for a moment—from God’s promises in order to attend to our own wants or needs or priorities. When this happens, we risk losing our awareness of God’s presence and action in our lives, choosing to focus instead on more tangible realities like food, possessions, pleasure, comfort, and reputation.

“Jésus tenté dans le désert” by James Tissot

In the desert, Jesus faces the same kinds of temptations that we face in our own lives. He is tempted to turn stones into bread—to satisfy immediate hunger and comfort rather than to trust in God. He is tempted to leap from the Temple—to use God as a safety net and to turn faith into a way of controlling outcomes instead of a way of trusting. And he is tempted with power over the kingdoms of the world—to choose influence and success over the quieter, harder path of humble faithfulness. None of these temptations are simply about doing something obviously wrong. They are about choosing what feels easier or more rewarding in the moment instead of choosing what leads us more deeply into trust in God.

The struggle is real. As Trappist writer Michael Casey has reflected, “We have been called to follow the one who was tempted in the desert, and we must expect that fidelity to our life of discipleship will involve us in substantial and sometimes earth-shuddering struggles.”

In the end, however, after being tempted to be self-sufficient and to use his power for his own glory, Jesus did not turn away from God—the will of the Father remained the priority of his life. Jesus’ response to the temptations he faced sets the standard for us as we navigate the daily realities of our own spiritual journeys.

The Season of Lent ultimately reminds us that holiness is possible for us only when we enter into the struggle, remembering that whatever darkness we may encounter will not overtake us as long as we refuse to accept anything less than God’s love and mercy.

Here we see why those traditional bona opera (“good works”) of Lent are so important, particularly because each of them contains a promise:

· Prayer re-centers our desires

· Fasting reveals what we rely on instead of God

· Almsgiving frees us from self-centeredness and directs us toward our neighbor

Lent is not simply about self-improvement or spiritual discipline for its own sake. It is about learning, again and again, to entrust our lives to the strange mercy of God—to let go of the illusion that we can save ourselves and to resist the subtle temptations to put comfort, control, or success in God’s place.

In the desert, Jesus shows us what faithful surrender looks like, and in the practices of Lent we are given a way to train our hearts in that same trust.

None of this removes the struggle from our lives—but Lent is forming us to meet that struggle with hope. Lent teaches us that the path of discipleship is not about avoiding the desert, but about learning how to walk through it with Christ, trusting that God’s mercy will be enough for us.

Grant, almighty God,

through the yearly observances of holy Lent,

that we may grow in understanding

of the riches hidden in Christ

and by worthy conduct pursue their effects.

Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son,

who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit,

God, for ever and ever. Amen.

-Collect for the First Sunday of Lent